A Publication of Churches Under Christ Ministry

Previous Lesson:

VI. The Period of Intolerance and Persecution in Virginia Ends in 1775 with the Beginning of the Revolution; The Baptists Push for Religious Freedom

Next Lesson:

VIII. Virginia Baptists Alone in Seeking Freedom of Conscience; The Battle for Soul Liberty in Virginia; Jefferson Fights for Religious Liberty

Click here for links to all lessons on “To Virginia.”

Click here to go to the written lessons.

Click here to go to the 3 1/2 to 6 minute video lectures.

For accompanying more thorough study from God Betrayed click here.

Jerald Finney

Copyright © March 3, 2018

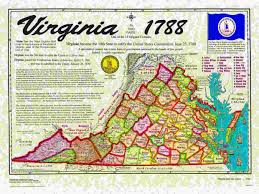

Virginia adopted a new constitution in 1776. The Convention of 1776 was, by its act, made the “House of Delegates” of the first General Assembly under the new constitution. Twenty-nine new members in this meeting were not in the 1775 Convention. “[W]hen there was anything near a division among the other inhabitants in a county, the Baptists, together with their influence, gave a caste to the scale, by which means many a worthy and useful member was lodged in the House of Assembly and answered a valuable purpose there.”[1] Among those favorable to Baptist causes was James Madison. On May 12, the Congress met in Philadelphia “and instructed the colonies to organize independent governments of their own. The war was on.” On May 15, the Convention resolved to declare the “colonies free and independent states” and that a committee be appointed to prepare Declaration of Rights and a plan of government which would “maintain peace and order” and “secure substantial and equal liberty to the people.”[2]

Other than Rhode Island, Virginia was the first colony to recognize religious liberty “in her organic law, and this she did in Article XVI. of her Bill of Rights, which was adopted on the 12th day of June 1776.”[3] In 1776, petitions from all over Virginia seeking religious freedom and freedom of conscience beset the Virginia state convention. Patrick Henry proposed the provision to section sixteen of the Virginia Bill of Rights, which granted religious tolerance.[4] On June 12, the House adopted a Declaration of Rights. The 16th Article provided for religious tolerance. However, [o]n motion on the floor by James Madison, the article was amended to provide for religious liberty. See [5] for short explanation of where Madison learned the distinction between religious toleration and religious liberty. In committee, Madison opposed toleration because toleration “belonged to a system where there was an established church, and where it was a thing granted, not of right, but of grace. He feared the power, in the hands of a dominant religion, to construe what ‘may disturb the peace, the happiness, or the safety of society,’ and he ventured to propose a substitute, which was finally adopted.”[6] He probably moved to change the amendment before the whole house in order to demonstrate his position to the Baptists who were viewing the proceedings. The  amendment as passed by the convention read:

amendment as passed by the convention read:

- “That religion, or the duty which we owe to our CREATOR, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and, therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.”[7]

“The adoption of the Bill of Rights marked the beginning of the end of the establishment.”[8]

Endnotes

[1] Charles F. James, Documentary History of the Struggle for Religious Liberty in Virginia (Harrisonburg, VA.: Sprinkle Publications, 2007; First Published Lynchburg, VA.: J. P. Bell Company, 1900), p. 58.

[2] Ibid., pp. 58-62.

[3] Ibid., p. 10.

[4] William H. Marnell, The First Amendment: Religious Freedom in America from Colonial Days to the School Prayer Controversy (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), pp. 94-95; James, pp. 62-65.

[5] Where did Madison learn the distinction between religious freedom and religious toleration? “It had not then begun to be recognized in treatises on religion and morals. He did not learn it from Jeremy Taylor or John Locke, but from his Baptist neighbors, whose wrongs he had witnessed, and who persistently taught that the civil magistrate had nothing to do with matters of religion.” (Charles F. James, Documentary History of the Struggle for Religious Liberty in Virginia (Harrisonburg, VA.: Sprinkle Publications, 2007; First Published Lynchburg, VA.: J. P. Bell Company, 1900), p. 63 quoting Dr. John Long.)[5]

Madison studied for the ministry at Princeton University, then the College of New Jersey, under John Witherspoon. When he returned to Virginia, he continued his theological interests and developed a strong concern for freedom of worship.

“At the time of Madison’s return from Princeton, several ‘well-meaning men,’ as he described them, were put in prison for their religious views. Baptists were being fined or imprisoned for holding unauthorized meetings. Dissenters were taxed for the support of the State Church. Preachers had to be licensed. Madison saw at first hand the repetition of the main evils of the Old Country. But he also saw a deep dissatisfaction among the people—the kind of dissatisfaction that would grow and that would serve as a mighty battering ram for religious freedom.” (Norman Cousins, In God We Trust (Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1958), p. 296.)

[6] See Lenni Brenner, editor, Jefferson and Madison on Separation of Church and State (Fort Lee, NJ: Barricade Books, Inc, 2004), pp. 21-22 for George Mason’s Article, Madison’s Amendment to Mason’s Article, The Proposal of Committee of Virginia’s Revolutionary Convention, Madison’s Amendment to the Committee’s Article, and the Article as Passed); James, pp. 62-65.

[7] James, pp. 62-64; Leo Pfeffer, Church, State, and Freedom (Boston: The Beacon Press, 1953), p. 96.

[8] Pfeffer, p. 96.