Jerald Finney

Copyright © January 18, 2012

Click here to go to links to all Chapters in Section V.

Note. This is an edited version on Section V, Chapter 4 of God Betrayed.

Separation of God and State: 1947-2007

Contents:

I. Introduction

II. The ACLU’s attacks on the recognition of God in state affairs

III. The 1947 Everson decision lays the groundwork for removal of God from all civil government affairs (for a pluralistic society that rejects the God of the Bible) by adding a new twist to the First Amendment “establishment clause” while still recognizing the original meaning of that clause

IV. An analysis of “religion clause” cases after Everson which have systematically removed the God of the Bible from practically all civil government affairs

V. Conclusion

I. Introduction

“Excessive power concentrated in the hands of sinful men is a formula for tyranny and disaster” (John Eidsmoe, God and Caesar: Biblical Faith and Political Action (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stack Publishers, 1997), pp. 16-17). The Founding Fathers attempted to prevent such a concentration of powers by balancing the power of civil government among legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Nonetheless, the modern Supreme Court, not to mention the President, has become an uncontrolled tyrant by usurping power not given it by the Constitution. Wicked presidents appoint wicked Supreme Court Justices who promote the President’s philosophy and agenda and are consented to by the Senate, even when composed of a majority of “conservatives.” Instead of interpreting law, the Court makes law and overturns legitimate laws made by the representatives of the people. Judges, like all men, vary all along the scale from good to bad. Some judges have been “mentally impaired, venal, and even racist” (Mark R. Levin, Men in Black: How the Supreme Court Is Destroying America (Washington DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 2005), pp. 1, 11-12). Most have been spiritually blind, guided by the god of this world. “As few as five justices can and do dictate economic, cultural, criminal, [spiritual] and security policy for the entire nation…” (Ibid.).

“Activist judges have taken over schools systems, prisons, private-sector hiring and firing practices, and farm quotas; they have ordered local governments to raise property taxes and states to grant benefits to illegal immigrants; they have expelled God, prayer, and the Ten Commandments from the public square; they’ve protected virtual child pornography, racial discrimination in law school admissions, flag burning, the seizure of private property without just compensation, [abortion,] and partial-birth abortion. They’ve announced that morality alone is an insufficient basis for legislation. Courts now second-guess the commander in chief in time of war and confer due process rights on foreign enemy combatants. They intervene in the electoral process” (Ibid.).

The Supreme Court in effect legislates and overturns constitutional laws passed by the state and federal governments, ignoring the constitutional constraints upon its authority. The tyrannical turn of the Court could have been predicted by anyone with a firm grasp of biblical principles. Even during the debates over ratification of the Constitution, some men predicted such a turn by the Court. For, example, Robert Yates, an ardent anti-federalist and delegate to the Constitutional Convention from New York, in opposing the Constitution, predicted the process by which the federal judiciary would achieve primacy over the state governments and other branches of the national government:

“Perhaps nothing could have been better conceived to facilitate the abolition of the state governments than the constitution of the judicial. They will be able to extend the limits of the general government gradually, and by insensible degrees, and to accommodate themselves to the temper of the people. Their decisions on the meaning of the constitution will commonly take place in cases which arise between individuals, with which the public will not be generally acquainted; one adjudication will form a precedent to the next, and this to a following one” (Ibid., pp. 27-29 citing Robert Yates, “Essay No. 11,” Anti-federalist Papers first published in the New York Journal, March 20, 1788. Available at http://www.constitution.org).

The balance of power intended by the founders was upset soon after ratification of the Constitution.

“In its 1803 Marbury v. Madison[, 5 U.S. 137 (1803)] decision, the Supreme Court determined that it had the power to decide cases about the constitutionality of congressional (or executive) actions and—when it deemed they violated the Constitution—overturn them. The shorthand label given to this Court-made authority is ‘judicial review.’ And this, quite literally, is the foundation for the runaway power exercised by the federal courts to this day…. [Chief Justice John] Marshall’s ruling in Marbury was nothing short of a counter-revolution. For 200 years, the elected branches have largely acquiesced to the judiciary’s tyranny” (Ibid., pp. 30, 33; see pp. 29-33 for an excellent overview of the history surrounding Marbury).

For a century and a half, Supreme Court and civil government interference with churches and attempts to make sure all vestiges of God were erased from public life were practically nonexistent. However, armed with the power of judicial review, the twentieth century Court, without the benefit of a biblical worldview, began to decide issues in a society which had abandoned many of its founding principles and to attempt to define the liberties and rights of the individual, of the minority and the majority, which had been based upon biblical principles—of which many or most of the Justices had no knowledge or understanding—written into the First Amendment. As a result, some of the Court’s assertions were and are correct but were polluted with unbiblical assertions and reasoning. The reasoning of the Court was applied in a society generally ignorant of biblical principles and which was becoming more secular with each passing day. “The application to particular factual situations of the … general rules [concerning the First Amendment religion clause as laid down by the Court], simplistic as they appear to be in the abstract, has involved a complex pattern of turns and twists of legal reasoning, cutting across almost all facets of human life” (Donald T. Kramer, J.D. Annotation: Supreme Court Cases Involving Establishment and Freedom of Religion Clauses of Federal Constitution, 37 L. Ed. 2d 1147 § 2. Kramer lists the “facets of human life” across which the religion clause as applied by the Court has cut. Then Kramer examines the cases. The reader of Kramer’s annotation must keep in mind that Kramer leaves God out of the analysis. A Christian who studies his annotation must also read and study the cases themselves (not just Kramer’s summaries and analyses) and analyze those cases in light of biblical principles. Kramer misses the most important point—the religion clause has been used to remove God from the public life of America and to insult God by eliminating Him from all consideration in civil government affairs.).

The foundational law, the Bible, agrees with a correct interpretation of the First Amendment, an interpretation which has never been fully applied by our courts or understood by the vast majority of Americans. Even Christian lawyers have looked to Court decisions, not the Bible, as the foundational law upon which they make their arguments and place their hope. The result has been a steady downward spiral toward a totally secular state and populace. Although “Christian” lawyers have sought to fight this downward spiral, for the most part they have fought in a manner, as exemplified in recent cases dealing with the display of the Ten Commandments on public property, which dishonors God. Even though “claiming” some “victories” in the legal arena, those “victories” are nothing more than compromises at best which chip away at or totally destroy recognition of the sovereignty of God, and lead deeper into a pluralistic state and society, while Christianity and the true and only God are degraded by civil government and society in general. At the same time that victories (which are rare and which are not victories) are being proclaimed by “Christian” lawyers, those lawyers and their firms are leading Bible believing pastors and church members, who have not studied the issues, down the road to destruction.

II. The ACLU’s attacks on the recognition of God in state affairs

The American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) has been the preeminent instigator of lawsuits attacking the recognition of God in state affairs. The ACLU first sends threatening letters to coerce schools, agencies of civil governments and others into terminating their practice which recognizes God. Should that fail, many times they initiate lawsuits, and many of those legal battles have gone all the way to the Supreme Court. Even should they lose in court, they, and their cohorts in the secular media and in society in general sometimes begin a mass disinformation campaign to turn the tide of public opinion and eventually the tide of the law. That tactic was successful after they lost the 1925 “Scopes Trial,” which involved a state law which punished by fine the teaching of evolution in the public school classroom in Tennessee (See Edward J. Larson, Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion (BasicBooks, A Member of the Perseus Books Group)). Only creationism was allowed to be taught in Tennessee. After the trial, in which a public school teacher who had supposedly taught evolution in a Tennessee classroom was convicted, popular writers falsely portrayed the fight as “science against a resistant fundamentalism which clung to the tenets of the Bible,” glorified science and belittled the Bible and those who believed it, portrayed the trial as a decisive defeat for old-time religion, and belittled witnesses in the trial who had been on the side of creationism while making secular saints of those on the other side.

Even then, although the great majority of the population was Christian, much of the media was liberal, having been given a closed-minded education in secular colleges and universities. Ultimately, fundamentalism withdrew from the main culture and constructed “a separate subculture with independent religious, educational, and social institutions” (Ibid., pp. 225-246).

- “For eight decades, the ACLU has been America’s leading religious censor, waging a largely uncontested (until recently) war against America’s core values—all not only without protest but with the support of much of the media—cloaking its war in the name of liberty.”

- “The result of this conflict is that Americans find themselves living in a country that, with each passing day, resembles less of what our nation’s Founding Fathers intended…. We now live in a country where our traditional Christian … faith and religion—civilizing forces in any society—are openly mocked and increasingly pushed to the margins. We live in a country where parental authority is undermined and children have less protection from pornography, violent crime, and the promotion of dangerous and selfish sexual behaviors. We live in a country where the value of human life has been cheapened—from the moment and manner of conception to natural or unnatural death” (Alan Sears and Craig Osten, The ACLU vs America (Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman & Holman Publishers 2005), p. 2).

When the results of this cheapening of human life and proliferation of the teaching of atheism and all manner of evil in the public schools rears its ugly head in the form of a perhaps elitist contrived mass murder by a state drugged victim of secular thought, secular society and evil leaders pounce upon the event to further its goal of setting up a world governance by waging an intense campaign of lies and deceit with the goal of taking all the guns; the reason—without the means to resist, those who oppose the goals of the elite and those who might do so can simply be eiliminated (murdered). This was the pattern in the Soviet Union, Germany under Hitler, Cambodia, Korea, etc.

In the area of religion, “in the last 40 years, [the ACLU] has banned school prayer (including silent meditation), eliminated graduation invocations, driven creches and menorahs from public parks, taken carols out of school assemblies, purged the Ten Commandments monuments, and … called into question God in the Pledge of Allegiance” (Ibid., citing Don Feder, “One Nation Under… ,” FrontPageMagazine.com, April 30, 2004).

The civil government supports humanism with its dollars. “If you doubt this, next time you go to a national park notice how much you and your children are exposed to the theory of evolution” (Eidsmoe, God and Caesar, p. 134). Books, displays, presentations, and tours promote evolution. The Supreme Court has banned God from the public schools, and the curricula of the public school classroom is based on the religion of humanism. Humanists know the importance of getting Satan’s message to the young. As one humanist leader puts it:

- “I am convinced that the battle for humankind’s future must be waged and won in the public school classroom by teachers who correctly perceive their role as the proselytizers of a new faith: a religion of humanity that recognizes and respects the spark of what theologians call divinity in every human being. These teachers must embody the same selfless dedication as the most rabid fundamentalist preacher, for they will be ministers of another servant, utilizing a classroom instead of a pulpit to convey humanist values in whatever subjects they teach regardless of the educational level—preschool daycare or large state university. The classroom must and will become an area of conflict between the old and the new—the rotting corpse of Christianity, together with all its adjacent evils and misery and the new faith of humanism resplendent in its promise of a world in which the never realized Christian idea of ‘love thy neighbor’ will finally be achieved” (Ibid., p. 136, citing John Dumphy, The Humanist, January/February 1983, p. 26. Quoted in Cal Thomas, Book Burning, (Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1983), p. 55).

III. The 1947 Everson decision lays the groundwork for removal of God from all civil government affairs (for a pluralistic society that rejects the God of the Bible) by adding a new twist to the First Amendment “establishment clause” while still recognizing the original meaning of that clause

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1, 67 S. Ct. 504, 91 L. Ed. 711, 1947 U.S. LEXIS 2959; 168 A.L.R. 1392 (1947) finished laying the groundwork for the secular pluralistic state, for totally eradicating all mention of God, at least of God as who He is, from civil governmental functions in America. Everson reached the same conclusion as Cochran v. Louisiana State Board of Education, 281 U.S. 370 (1930), but by a different rationale.

In Meyer and Pierce, the First Amendment, as implemented by the Fourteenth, established the right of religious minorities to send their children to parochial schools. In Cochran and Everson, the right of minorities attending church-operated schools to share in the benefits of social legislation was established.

A Bible-believing Christian should ask, “Why was there a public school in a supposedly Christian nation since civil government was given no authority by God to educate children and since God had placed such responsibility in the hands of parents?” Obviously, the nation began early to move away from God’s principles. As could be anticipated, the movement of the public schools away from God began not long after their origin in this nation.

“[T]he religion of the public schools has changed. In the 1700s, the religion of American education was orthodox and mostly Calvinist Christianity. In the 1800s this religion was replaced by a more liberalized version of Christianity bordering on Unitarianism. And in the twentieth century the religion of the American public schools appears to be something closer to secular humanism” (Eidsmoe, God and Caesar, pp. 150-151).

The issue in Cochran was whether taxation by the state of Louisiana for the purchase of school books for school children including school children going to private, religious, sectarian, and other schools not embraced in the public educational system violated the First Amendment. The Court, in a unanimous decision delivered by Chief Justice Hughes,

“drew a distinction among the People, the State, and the Church. It held that there was no violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in a specific legislative act designed to benefit the people and the State…. The fact of education benefits the people and the State; that it may also benefit the Church is a correlative fact but not an indistinguishable one. So long as the textbooks lent were the same ones lent in the public schools and so long as they were lent for the same purpose, education in the areas of secular study, the act was a piece of social legislation within the constitutional prerogative of the State…. If a piece of legislation aids the People and the State but does not aid the Church directly, it is constitutional” (William H. Marnell, The First Amendment: Religious Freedom in America from Colonial Days to the School Prayer Controversy (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), pp. 167-168, 172).

All the cases considered in the last article on this blog (Chapter 3 of God Betrayed), and in this article to this point, dealt with the protection of religious rights of minorities under the “free exercise clause.” Everson was decided under the “establishment clause.” Everson completely changed the meaning of “establishment of religion.”

The issue in Everson was whether the state could use tax money to reimburse the parents of children who attended a church school for their bus fares for riding to school. The majority reached the same conclusion as did Cochran, but using a different rationale.

“[The People] and [the Church] were fused in contradistinction to the [State], in the majority opinion as well as in the minority. Out of this fusion emerges a new pattern of thinking. Does the Constitution forbid an establishment of religion, or does it forbid an establishment of religion? … When the word establishment is italicized, the phrase has a definite historical meaning. An establishment is a state-supported church[.] But when the word religion is italicized, then an undetermined and indeterminable swarm of implications, inferences, corollaries, and conclusions emerges from the philological cacoon. They began to merge in 1948” (Ibid., pp. 172, 175-176).

The majority and minority in Everson agreed that any aid to a church through legislation that was intended to aid the people and the state was “an establishment of religion” which was forbidden by the Constitution. The majority thought that the bus fare paid for students riding to parochial schools did not aid the church. The minority disagreed.

Thus, with Everson, “establishment of religion” became something entirely different from what it had been to that point. As described by Marnell in the above quote, “establishment of religion” or establishment of a state supported church became “establishment of religion,” which was something entirely different. The court further stated that the Constitution created “a wall of separation between church and state” (Everson, 330 U.S. 1 at 16; 67 S. Ct. 504, 91 L. Ed. 711, 1947 U.S. LEXIS 2959; 168 A.L.R. 1392 (1947)). Eventually, this rationale, all taken together, while honoring the historical First Amendment and biblical principle of separation of church and state, would also lead to the removal, or the attempt to remove, any vestige of God from civil government affairs—something which the history surrounding the time of ratification of the Constitution soundly disproves; obviously, the Constitution did not require the removal of the God of the Bible from civil government affairs although it did put a wall between church and state, a wall which was breached by churches who readily submitted themselves to the state for alleged benefits. Even when the Court would allow the mention of God, it was with the understanding that it was only historical and of no significance. God, the Ruler of the universe, the Ultimate Lawmaker, and the Judge of the Supreme Court of the universe, gave United States Supreme Court justices the right to rebel against His authority.

Supreme Court Justices in the 1940s were operating in a nation where the underlying framework of civil government had already been remolded into something contrary to the principles of God concerning civil government and something not allowed by the Constitution—the federal government was aiding individuals through all types of social legislation. Justice Black, in the majority opinion in Everson, commented upon some of the changes in direction the nation had taken:

- “It is true that this Court has, in rare instances, struck down state statutes on the ground that the purpose for which tax-raised funds were to be expended was not a public one…. But the Court has also pointed out that this far-reaching authority must be exercised with the most extreme caution…. Otherwise, a state’s power to legislate for the public welfare might be seriously curtailed, a power which is a primary reason for the existence of states. Changing local conditions create new local problems which may lead a state’s people and its local authorities to believe that laws authorizing new types of public services are necessary to promote the general well-being of the people. The Fourteenth Amendment did not strip the states of their power to meet problems previously left for individual solution.

- “It is much too late to argue that legislation intended to facilitate the opportunity of children to get a secular education serves no public purpose…. Nor does it follow that a law has a private rather than a public purpose because it provides that tax-raised funds will be paid to reimburse individuals on account of money spent by them in a way which furthers a public program…. Subsidies and loans to individuals such as farmers and home-owners, and to privately owned transportation systems, as well as many other kinds of businesses, have been commonplace practices in our state and national history” (Ibid., pp. 6-7).

As to the issue of separation of church and state, as pointed out in the above statement and in the dissent, states were now taxing to support individuals. Prior to independence and the Constitution, the colonies had done this, but with a difference. The difference—the money to support members of the public went to churches in the colonies and the churches used the money to pay ministers, build church buildings, and support charities. Tax money now went to government agencies, whose religion was secular humanism and which were becoming the new source of help and instruction for many Americans. The United States went from one type of illegal and destructive taxation to another. On the national level, the New Deal spearheaded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt had gone far in replacing a faith in God with a faith in government. President Roosevelt, with his proposed court-packing scheme, coerced the Justices of the Supreme Court into going along with his civil government programs. The nation was switching from the way of faith in God to the way of faith in the god of this world; and, in its instructive capacity, was leading the people down the same path.

Bible believing Christians should note that Supreme Court Justices and other government officials and agents who were not operating under God were called upon to formulate principles to guide its citizens. Supreme Court Justices in Everson were deciding an issue by incorrectly using underlying First Amendment law which had come about as a result of a spiritual conflict and which reflected a biblical principle in a nation that was becoming more and more divorced from God’s principles.

The majority opinion in Everson, of course, contained some truth in reaching its unconstitutional and unbiblical conclusion. The god of this world has from the beginning been a master of deceit and always introduces some truth into the debate. Justice Black, writing for the majority, and the dissent written by Justice Rutledge, selectively extracted accurate portions of First Amendment history while leaving out vital aspects. Justice Black wrote:

- “A large proportion of the early settlers of this country came here from Europe to escape the bondage of laws which compelled them to support and attend government-favored churches. The centuries immediately before and contemporaneous with the colonization of America had been filled with turmoil, civil strife, and persecutions, generated in large part by established sects determined to maintain their absolute political and religious supremacy. With the power of government supporting them, at various times and places, Catholics had persecuted Protestants, Protestants had persecuted Catholics, Protestant sects had persecuted other Protestant sects, Catholics of one shade of belief had persecuted Catholics of another shade of belief, and all of these had from time to time persecuted Jews. In efforts to force loyalty to whatever religious group happened to be on top and in league with the government of a particular time and place, men and women had been fined, cast in jail, cruelly tortured, and killed. Among the offenses for which these punishments had been inflicted were such things as speaking disrespectfully of the views of ministers of government-established churches, non-attendance at those churches, expressions of non-belief in their doctrines, and failure to pay taxes and tithes to support them.

- “These practices of the old world were transplanted to and began to thrive in the soil of the new America. The very charters granted by the English Crown to the individuals and companies designated to make the laws which would control the destinies of the colonials authorized these individuals and companies to erect religious establishments which all, whether believers or non-believers, would be required to support and attend. An exercise of this authority was accompanied by a repetition of many of the old-world practices and persecutions. Catholics found themselves hounded and proscribed because of their faith; Quakers who followed their conscience went to jail; Baptists were peculiarly obnoxious to certain dominant Protestant sects; men and women of varied faiths who happened to be in a minority in a particular locality were persecuted because they steadfastly persisted in worshipping God only as their own consciences dictated. And all of these dissenters were compelled to pay tithes and taxes to support government-sponsored churches whose ministers preached inflammatory sermons designed to strengthen and consolidate the established faith by generating a burning hatred against dissenters.

- “These practices became so commonplace as to shock the freedom-loving colonials into a feeling of abhorrence. The imposition of taxes to pay ministers’ salaries and to build and maintain churches and church property aroused their indignation. It was these feelings which found expression in the First Amendment. No one locality and no one group throughout the Colonies can rightly be given entire credit for having aroused the sentiment that culminated in adoption of the Bill of Rights’ provisions embracing religious liberty. But Virginia, where the established church had achieved a dominant influence in political affairs and where many excesses attracted wide public attention, provided a great stimulus and able leadership for the movement. The people there, as elsewhere, reached the conviction that individual religious liberty could be achieved best under a government which was stripped of all power to tax, to support, or otherwise to assist any or all religions, or to interfere with the beliefs of any religious individual or group.

- “The movement toward this end reached its dramatic climax in Virginia in 1785-86 when the Virginia legislative body was about to renew Virginia’s tax levy for the support of the established church. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison led the fight against this tax. Madison wrote his great Memorial and Remonstrance against the law. In it, he eloquently argued that a true religion did not need the support of law; that no person, either believer or non-believer, should be taxed to support a religious institution of any kind; that the best interest of a society required that the minds of men always be wholly free; and that cruel persecutions were the inevitable result of government-established religions. Madison’s Remonstrance received strong support throughout Virginia, and the Assembly postponed consideration of the proposed tax measure until its next session. When the proposal came up for consideration at that session, it not only died in committee, but the Assembly enacted the famous ‘Virginia Bill for Religious Liberty’ originally written by Thomas Jefferson. [Quotations from the ‘Virginia Bill for Religious Liberty’ follow in the opinion.]” (Ibid., pp. 8-14).

The majority gave its interpretation of the meaning of the First Amendment:

“The ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between church and State.’ Reynolds v. United States, supra at 164…” (Ibid., pp. 15-16). [Emphasis mine.]

Then, the majority upheld the New Jersey law which required the state to aid parents of students of Catholic schools, in effect aiding not only parents, but also a “church.”

- “New Jersey cannot consistently with the ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment contribute tax-raised funds to the support of an institution which teaches the tenets and faith of any church. On the other hand, other language of the amendment commands that New Jersey cannot hamper its citizens in the free exercise of their own religion. Consequently, it cannot exclude individual Catholics, Lutherans, Mohammedans, Baptists, Jews, Methodists, Non-believers, Presbyterians, or the members of any other faith, because of their faith, or lack of it, from receiving the benefits of public welfare legislation. While we do not mean to intimate that a state could not provide transportation only to children attending public schools, we must be careful, in protecting the citizens of New Jersey against state-established churches, to be sure that we do not inadvertently prohibit New Jersey from extending its general state law benefits to all its citizens without regard to their religious belief.

- “Measured by these standards, we cannot say that the First Amendment prohibits New Jersey from spending tax-raised funds to pay the bus fares of parochial school pupils as a part of a general program under which it pays the fares of pupils attending public and other schools. It is undoubtedly true that children are helped to get to church schools. There is even a possibility that some of the children might not be sent to the church schools if the parents were compelled to pay their children’s bus fares out of their own pockets when transportation to a public school would have been paid for by the State. The same possibility exists where the state requires a local transit company to provide reduced fares to school children including those attending parochial schools, or where a municipally owned transportation system undertakes to carry all school children free of charge. Moreover, state-paid policemen, detailed to protect children going to and from church schools from the very real hazards of traffic, would serve much the same purpose and accomplish much the same result as state provisions intended to guarantee free transportation of a kind which the state deems to be best for the school children’s welfare. And parents might refuse to risk their children to the serious danger of traffic accidents going to and from parochial schools, the approaches to which were not protected by policemen. Similarly, parents might be reluctant to permit their children to attend schools which the state had cut off from such general government services as ordinary police and fire protection, connections for sewage disposal, public highways and sidewalks. Of course, cutting off church schools from these services, so separate and so indisputably marked off from the religious function, would make it far more difficult for the schools to operate. But such is obviously not the purpose of the First Amendment. That Amendment requires the state to be a neutral in its relations with groups of religious believers and non-believers; it does not require the state to be their adversary. State power is no more to be used so as to handicap religions than it is to favor them.

- “This Court has said that parents may, in the discharge of their duty under state compulsory education laws, send their children to a religious rather than a public school if the school meets the secular educational requirements which the state has power to impose. See Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510. It appears that these parochial schools meet New Jersey’s requirements. The State contributes no money to the schools. It does not support them. Its legislation, as applied, does no more than provide a general program to help parents get their children, regardless of their religion, safely and expeditiously to and from accredited schools” (Ibid., pp. 15-18).

True, the state has the power, but not the God-given authority, to enforce secular educational requirements. Then, Justice Black wrote:

- “The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach. New Jersey has not breached it here” (Ibid., p. 18). [Emphasis mine.]

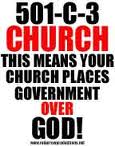

The effect of the new rationale regarding separation of church and state was twofold. First, the Court still honored biblical separation of church and state. A church can operate under God if it so chooses. That “high and impregnable” wall allows both the civil government and a church, according to their individual choices, to remain under God only. Civil government is not over a church—if a church so chooses—and a church is not over civil government. Sadly, most churches eagerly submit to civil government by incorporating and applying for 501(c)(3) status.

Second, the opinion laid the groundwork for removal of God from the public life of America. Mr. Justice Jackson’s dissent, joined by Mr. Justice Rutledge was prophetical:

- “The Court’s opinion marshals every argument in favor of state aid and puts the case in its most favorable light, but much of its reasoning confirms my conclusions that there are no good grounds upon which to support the present legislation. In fact, the undertones of the opinion, advocating complete and uncompromising separation of Church from State, seem utterly discordant with its conclusion yielding support to their commingling in educational matters. The case which irresistibly comes to mind as the most fitting precedent is that of Julia who, according to Byron’s reports, ‘whispering ‘I will ne’er consent,’ – consented’” (Ibid., p. 19).

- “Thus, under the Act and resolution brought to us by this case, children are classified according to the schools they attend and are to be aided if they attend the public schools or private Catholic schools, and they are not allowed to be aided if they attend private secular schools or private religious schools of other faiths…. If we are to decide this case on the facts before us, our question is simply this: Is it constitutional to tax this complainant to pay the cost of carrying pupils to Church schools of one specified denomination? … [States] cannot, through school policy any more than through other means, invade rights secured to citizens by the Constitution of the United States. West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624. One of our basic rights is to be free of taxation to support a transgression of the constitutional command that the authorities ‘shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof ….’ U.S. Const.

- “The function of the Church school is a subject on which this record is meager. It shows only that the schools are under superintendence of a priest and that ‘religion is taught as part of the curriculum.’ But we know that such schools are parochial only in name — they, in fact, represent a world-wide and age-old policy of the Roman Catholic Church. Under the rubric ‘Catholic Schools,’ the Canon Law of the Church, by which all Catholics are bound, provides concerning the education of Catholic children, among other things, that the Catholic faith and morals are to be taught in Catholic schools; that the religious teaching of youth in any schools is subject to the authority and inspection of the Church” (Ibid., pp. 20-23).

- “The state cannot maintain a Church and it can no more tax its citizens to furnish free carriage to those who attend a Church. The prohibition against establishment of religion cannot be circumvented by a subsidy, bonus or reimbursement of expense to individuals for receiving religious instruction and indoctrination.

“The Court, however, compares this to other subsidies and loans to individuals and says, ‘Nor does it follow that a law has a private rather than a public purpose because it provides that tax-raised funds will be paid to reimburse individuals on account of money spent by them in a way which furthers a public program.’ Of course, the state may pay out tax-raised funds to relieve pauperism, but it may not under our Constitution do so to induce or reward piety. It may spend funds to secure old age against want, but it may not spend funds to secure religion against skepticism. It may compensate individuals for loss of employment, but it cannot compensate them for adherence to a creed. - “It seems to me that the basic fallacy in the Court’s reasoning, which accounts for its failure to apply the principles it avows, is in ignoring the essentially religious test by which beneficiaries of this expenditure are selected. A policeman protects a Catholic, of course — but not because he is a Catholic; it is because he is a man and a member of our society. The fireman protects the Church school — but not because it is a Church school; it is because it is property, part of the assets of our society. Neither the fireman nor the policeman has to ask before he renders aid ‘Is this man or building identified with the Catholic Church’” (Ibid., pp. 23-25)?

Mark R. Levin points out that Justice Black, a former Ku Klux Klan member who probably hated the Catholic Church, wrote the majority opinion “for the purpose of undercutting the true meaning of the religion clauses.” He “joined the majority in order to thwart them from the inside—and he succeeded.”

“[Justice Black’s opinion in Everson] drew criticism from all quarters. Black’s rhetoric and dicta contrasted too sharply with his conclusion and holding to satisfy anyone. If he had not written it as he did, he later said, ‘[Supreme Court Justice Robert] Jackson would have. I made it as tight and gave them as little room to maneuver as I could.’ [Justice Black] regarded it as going to the verge. His goal, he remarked at the time, was to make it a Pyrrhic victory and he quoted King Pyrrhus, ‘One more victory and I am undone’” (Levin, pp. 42-43 quoting Roger K. Newman, Hugo Black, A Biography (New York: pantheon Books, 1994)).

Liberals still constantly rely on Jefferson’s words, “wall of separation between church and state,” to justify their opposition to virtually any civil government intersection with God. If indeed Justice Black’s motivation was to hurt the Catholic Church, he instead hurt the nation by laying the groundwork for the severing of a recognition of the biblical doctrine of the sovereignty of God and an incorrect extension of the biblical doctrines of “government,” “church,” and “separation of church and state,” doctrines alien to the Catholic Church.

The Court was adopting the First Amendment to the conditions of a civil government that had gone outside its God-given and constitutional boundaries. All religions were to be treated equally and obviously to be given equal deference. Although the “wall of separation” originated by this Court still allowed a church to remain under God, when and if applied consistently, that wall would also be used to assure that God would not be honored as Supreme Sovereign by the United States of America. The new aspect of the First Amendment would ultimately result in chaos, especially since the other branches opened the door for churches to subjugate themselves to the civil government, as is shown in Section VI of God Betrayed which is reproduced on this website.

Even though a church can still choose to be under God only, most have chosen—by incorporating and taking “tax exemption” under an unconstitutional act of the federal government—not to do so. Justice Rehnquist was correct in stating that “[t]he ‘wall of separation between church and State’ [as interpreted by the Everson Court] is a metaphor based on bad history, a metaphor which has proved useless as a guide to judging. It should be frankly and explicitly abandoned” (Ibid., p. 45, quoting Justice Rehnquist in Wallace v. Jeffree, 472 U.S. 38, 107 (1985)). “Despite this, the ‘wall’ is part of the lexicon of many Supreme Court cases that involve religion and it has led to an inconsistent and illogical series of decisions” (Ibid.). However, one must keep in mind that the decision was partially correct in that it still proclaims that churches may choose to be under God because of the “high and impregnable wall” between church and state.

IV. An analysis of “religion clause” cases after Everson which have systematically removed the God of the Bible from practically all civil government affairs

Many cases between the decision in Everson in 1947 and the present continued to separate God and state. First, the federal and state governments had extended their authorities into areas where they were given no authority by God, into areas God desired to be left under the authority of governments other than civil government. Then the “impregnable wall of separation between church and state” was used to separate God from the United States of America. America made its God-allowed choice. The nation and its unlawful institutions and agencies are more and more guided by secular Godless and unbiblical principles.

A biblical examination of Supreme Court jurisprudence involving the removal of the nation from under God would be voluminous (See Kramer, 37 L. Ed. 2d 1147. This is an excellent summary of the cases involved. However, for a Christian to do the correct biblical and God-honoring analysis, he must read and analyze the cases from a biblical perspective.). The cases following in this chapter are just a sampling, with two 2005 cases involving public display of the Ten Commandments examined in some detail to show the depraved state of Supreme Court “separation of church and state” jurisprudence.

The “undetermined and indeterminable swarm of implications, inferences, corollaries, and conclusions which emerges from the philological cacoon” brought about by the newly defined establishment of religion began to emerge in 1948 in the McCollum case (Marnell, p. 176, citing Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948)). The released time law of the state of Illinois provided for voluntary attendance by students whose parents agreed to allow their children to attend such instruction at thirty or forty-five minute religious classes conducted in the classrooms of public schools. The teachers of such classes were volunteers of various religions approved by school authorities who provided their services at no expense to the schools. Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish classes were conducted, and other religions could have established classes under the law had there been a demand. The issue in McCollum was whether the state could use its power “to utilize its tax-supported public school system in aid of religious instruction insofar as that power may be restricted by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.” The five-judge majority wrote:

- “This is beyond all question a utilization of the tax-established and tax-supported public school system to aid religious groups to spread their faith. And it falls squarely under the ban of the First Amendment (made applicable to the States by the Fourteenth) as we interpreted it in Everson v. Board of Education…. There we said: ‘Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force or influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or nonattendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups, and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between Church and State’” (McCollum, 333 U.S. at 210-211). [Emphasis mine.]

Although the Supreme Court retreated somewhat from its Everson position in 1952, since Everson, America has been sliding down hill and away from recognition of God at an accelerating pace. In Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952), the Court upheld a New York law which allowed schools to dismiss students for religious instruction given off campus and financed entirely by churches. The issue was “whether New York by this system has either prohibited the ‘free exercise’ of religion or has made a law ‘respecting an establishment of religion’ within the meaning of the First Amendment” (Ibid., p. 310).

The Court, as it has done many times, demonstrated its misunderstanding of the difference between “separation of church and state” and “separation of God and state” by equating the two:

- “The First Amendment, however, does not say that in every and all respects there shall be a separation of Church and State. Rather, it studiously defines the manner, the specific ways, in which there shall be no concert or union or dependency one on the other…. Prayers in our legislative halls; the appeals to the Almighty in the messages of the Chief Executive; the proclamations making Thanksgiving Day a holiday; ‘so help me God’ in our courtroom oaths – these and all other references to the Almighty that run through our laws, our public rituals, our ceremonies would be flouting the First Amendment. A fastidious atheist or agnostic could even object to the supplication with which the Court opens each session: ‘God save the United States and this Honorable Court’” (Ibid., pp. 312-313).

Church and God are not the same. The First Amendment deals with separation of church and state, not separation of God and state. This seems such a simple truth; but one which, like God’s simple plan of salvation, has eluded many brilliant but foolish and vain religious and non-religious men.

- “Let no man deceive himself. If any man among you seemeth to be wise in this world, let him become a fool, that he may be wise. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God. For it is written, He taketh the wise in their own craftiness. And again, The Lord knoweth the thoughts of the wise, that they are vain. Therefore let no man glory in men…” (1 Co. 3.18-21).

To replow some ground, God the Son, the Lord Jesus Christ, instituted the church, with Himself to be over each local church. When He instituted the church, He had already instituted civil government and made known that He desired that each nation choose to submit itself to His sovereignty. Prayers, references, oaths, messages of chief executives, etc. have nothing to do with the establishment of a church. If made with proper motive to the God of the universe who has revealed Himself in the Bible, they have to do with recognition of and submission to the Sovereign of the universe.

Zorach demonstrated that, even though temporarily retreating somewhat from its Everson position, the Court, ignorant of truth, was unknowingly confused and at odds with its Sovereign. The Court continued:

“We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being. We guarantee the freedom to worship as one chooses. We make room for as wide a variety of beliefs and creeds as the spiritual needs of man deem necessary. We sponsor an attitude on the part of government that shows no partiality to any one group and that lets each flourish according to the zeal of its adherents and the appeal of its dogma. When the state encourages religious instruction or cooperates with religious authorities by adjusting the schedule of public events to sectarian needs, it follows the best of our traditions…. The government must be neutral when it comes to competition between sects. It may not thrust any sect on any person. It may not make a religious observance compulsory. It may not coerce anyone to attend church, to observe a religious holiday, or to take religious instruction. But it can close its doors or suspend its operations as to those who want to repair to their religious sanctuary for worship or instruction. No more than that is undertaken here” (Zorach, pp. 313-314).

If “we are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being,” then why do not the Court and the nation bow down to that Supreme Being? “Supreme” means “highest in rank or authority” (WEBSTER’S COLLEGIATE DICTIONARY 1185 (10th ed. 1995)). Maybe it is because we are, for the most part, “religious” but lost. The apostle Paul said:

- “But if our gospel be hid, it is hid to them that are lost: In whom the god of this world hath blinded the minds of them which believe not, lest the light of the glorious gospel of Christ, who is the image of God, should shine unto them” (2 Co. 4.3-4).

The retreat in Zorach was only temporary. Gradually Satan’s principles and activities were implemented, taught, and encouraged by the Supreme Court. In 1961, in McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 6 L. Ed. 2d 393, 81 S. Ct. 1101 (1961) the Supreme Court secularized the “Sabbath:”

- “Indeed, the purpose apparent from government action can have an impact more significant than the result expressly decreed: when the government maintains Sunday closing laws, it advances religion only minimally because many working people would take the day as one of rest regardless, but if the government justified its decision with a stated desire for all Americans to honor Christ, the divisive thrust of the official action would be inescapable. This is the teaching of McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 6 L. Ed. 2d 393, 81 S. Ct. 1101 (1961), which upheld Sunday closing statutes on practical, secular grounds after finding that the government had forsaken the religious purposes behind centuries-old predecessor laws. Id., at 449-451, 6 L. Ed. 2d 393, 81 S. Ct. 1101” (McCreary County, Kentucky, v. ACLU, 545 U.S. 844, 860-861 (2005)).

In Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961)), Leo Pfeffer and Lawrence Speiser argued the cause for appellant who was denied a commission as notary public in Maryland because he would not declare his belief in God. The Maryland Constitution provided that “[N]o religious test ought ever to be required as a qualification for any office of profit or trust in this State, other than a declaration of belief in the existence of God…” (Ibid., p. 489). The Supreme Court wrote:

- “The power and authority of the State of Maryland thus is put on the side of one particular sort of believers – those who are willing to say they believe in ‘the existence of God.’ … When our Constitution was adopted, the desire to put the people ‘securely beyond the reach’ of religious test oaths brought about the inclusion in Article VI of that document of a provision that ‘no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.’ … This Maryland religious test for public office unconstitutionally invades the appellant’s freedom of belief and religion [under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution] and therefore cannot be enforced against him” (Ibid., pp. 490, 491, 496).

The Court, as did our forefathers, related a belief in the Sovereign of the universe with “religious test.”

The Court further noted:

“In discussing Article VI in the debate of the North Carolina Convention on the adoption of the Federal Constitution, James Iredell, later a Justice of this Court, said:

- “… [I]t is objected that the people of America may, perhaps, choose representatives who have no religion at all, and that pagans and Mahometans may be admitted into offices. But how is it possible to exclude any set of men, without taking away that principle of religious freedom which we ourselves so warmly contend for” (Ibid., fn. 10, p. 495)?

- “Among religions in this country which do not teach but would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God are Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism, and others” (Ibid., fn. 11, p. 495).

Under the First Amendment, as it was intended, followers of humanism, and all followers of any other false religion were intended to be given freedom from persecution because of their beliefs. God desires that no one come to Him by force. However, the 1961 Court failed to know that there is but one God, but one Sovereign of the universe, Sovereign of nations, individuals, families, religious institutions and churches. The Court failed to understand the certain consequences brought by the failure of Judges of the Supreme Court, all civil government officials, and all people everywhere to choose to recognize Him as Sovereign.

In Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962) the Court declared that prayer in public school breaches the constitutional wall between church and state (). State officials wrote the following prayer which was required to be said aloud by each class in the presence of a teacher at the beginning of each school day:

- “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country” (Ibid., p. 422).

Satan is not satisfied with merely the watering down of prayer and failure to recognize God the Son. He hates to hear the name of the God of the Bible in any form. The state of New York had made every attempt to adapt a non-sectarian prayer.

- “Every effort was made in New York to adapt what was considered a traditional American right to the mid-twentieth-century situation in the state. The churches of the state were broadly represented in the composition of the prayer. It was limited in its theological foundation to the expression of a belief in God and a belief that human welfare was His concern. It represented, as well as human care could achieve, a non-sectarian common denominator of religious belief. It did affirm, however, a belief in God and in His providence. This belief conflicted with a minority belief…. The minority had a right not to say it, but in the view of the Court that was not enough. The Engel decision translated a minority right into minority rule” (Marnell, pp. 193-194).

The Court stated:

- “[W]e think that the constitutional prohibition against laws respecting an establishment of religion must at least mean that in this country it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by government” (Engel, 370 U.S. at 425).

One statement of the Court in Engel shows its total ignorance of the history, issues, and principles involved:

- “It is true that New York’s establishment of its Regents’ prayer as an officially approved religious doctrine of that State does not amount to a total establishment of one particular religious sect to the exclusion of all others – that, indeed, the governmental endorsement of that prayer seems relatively insignificant when compared to the governmental encroachments upon religion which were commonplace 200 years ago” (Ibid., p. 436).

That is an incredibly arrogant and misinformed statement indeed. One can interpret this to mean that the Court declares that the founders were more guilty of violating the First Amendment than were those who formulated the New York prayer being struck down!

In 1963, the Court in Abington v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963) again, as in McCollum and cases since, placed minority rights above the rights of the majority. The Court struck down state laws requiring the reading of Bible verses to students each day and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in the public schools. Two cases were combined. The Bible reading case was initiated in Abington Township, Pennsylvania, by Edward and Sidney Schempp. The Lord’s Prayer case was initiated by Madalyn Murray and her son William J. Murray, two professed atheists. At trial, parents Edward Lewis Schempp, his wife Sidney, and their children testified that as to specific religious doctrines purveyed by a literal reading of the Bible “which were contrary to the religious beliefs which they held and to their familial teaching” (Ibid, p. 208). An “expert” testified:

- “Dr. Solomon Grayzel testified that there were marked differences between the Jewish Holy Scriptures and the Christian Holy Bible, the most obvious of which was the absence of the New Testament in the Jewish Holy Scriptures. Dr. Grayzel testified that portions of the New Testament were offensive to Jewish tradition and that, from the standpoint of Jewish faith, the concept of Jesus Christ as the Son of God was ‘practically blasphemous…. Dr. Grayzel gave as his expert opinion that such material from the New Testament could be explained to Jewish children in such a way as to do no harm to them. But if portions of the New Testament were read without explanation, they could be, and in his specific experience with children Dr. Grayzel observed, had been, psychologically harmful to the child and had caused a divisive force within the social media of the school’” (Ibid., p. 209).

As it was in the times of Christ and the infant church, so it remains. The Jewish religion used the arm of the state to crucify Christ and to persecute His followers after His resurrection and ascension. “[T]he unbelieving Jews stirred up the Gentiles, and made their minds evil affected against the brethren” (Ac. 14.2). Jewish religious leaders have always opposed and been offended by the Lord Jesus Christ, but this nation arose because of true believers who stood on New and Old Testament principles, including the Lordship of Christ. Just as those who practiced Judaism crucified Christ in a nation destroyed because of their rebellion against God, unbelieving Jews continue their rebellion in America, many of whose founders and citizens believed in New and Old Testament principles, and as a result provided for religious freedom for all men, including religious Jews. (Note. Although the Jewish religious leaders acted to have Christ crucified, the sin of every man and woman was responsible for His crucifixion. He laid down His life that all who believe in Him would be saved.)

As to the purpose of the First Amendment, the Court quoted Mr. Justice Rutledge, joined by Justices Frankfurter, Jackson and Burton from the Everson opinion:

- “The [First] Amendment’s purpose was not to strike merely at the official establishment of a single sect, creed or religion, outlawing only a formal relation such as had prevailed in England and some of the colonies. Necessarily it was to uproot all such relationships. But the object was broader than separating church and state in this narrow sense. It was to create a complete and permanent separation of the spheres of religious activity and civil authority…” (374 U.S. at 217, citing Everson, p. 26). [Emphasis mine.]

How could the Court be any clearer in its statement of its 1947 Everson principle of separation of God and state—that is, in its renunciation of God over civil affairs?

The Court decided the case based upon the “establishment clause” and not on the “free exercise” clause which would have required a showing of coercion, according to the Court. Since the reading of the Bible and recitation of the Lord’s prayer were prescribed as classroom activities, the Court held that “the exercising and the law requiring them are in violation of the establishment clause” (Ibid.).

Not knowing that they were bucking the sovereign God, the Court belittled God and His principles by both its rationale and its conclusions. The Court in Abington stated that the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like (Ibid., p. 225). In other words, The Bible cannot be taught as the Word of God in a public school classroom.

In Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York, 397 U.S. 664 (1970), another example of such lunacy, an owner of real estate in Richmond County, New York, sought an injunction in the New York courts to prevent the New York City Tax Commission from granting property tax exemptions to religious organizations for religious properties used solely for religious worship. The Court upheld the state law, stating that the law did not violate the First Amendment. Explaining that complete separation was impossible, but that neutrality was necessary, the Court declared:

- “The legislative purpose of the property tax exemption is neither the advancement nor the inhibition of religion; it is neither sponsorship nor hostility. New York, in common with the other States, has determined that certain entities that exist in a harmonious relationship to the community at large, and that foster its ‘moral or mental improvement,’ should not be inhibited in their activities by property taxation or the hazard of loss of those properties for nonpayment of taxes. It has not singled out one particular church or religious group or even churches as such; rather, it has granted exemption to all houses of religious worship within a broad class of property owned by nonprofit, quasi-public corporations which include hospitals, libraries, playgrounds, scientific, professional, historical, and patriotic groups. The State has an affirmative policy that considers these groups as beneficial and stabilizing influences in community life and finds this classification useful, desirable, and in the public interest. Qualification for tax exemption is not perpetual or immutable; some tax-exempt groups lose that status when their activities take them outside the classification and new entities can come into being and qualify for exemption” (397 U.S. at 672-673). [Emphasis mine.]

The justices equated property owned by God’s church with other property owned by nonprofit, quasi-public corporations which include hospitals, libraries, playgrounds, scientific, professional, historical, and patriotic groups. A Christian should understand that the church, a spiritual entity, should never own any property (See Sections II, III, and VI of God Betrayed. These sections are reproduced on this website). Sadly, as is shown in Section VI of God Betrayed, although churches in America can occupy property in a manner which pleases God, most churches choose to hold property as owners under the plan laid out by the Satan through the civil government.

The Court in 1980, in Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39 (1980), held that a Kentucky statute requiring the posting of a copy of the Ten Commandments, purchased with private contributions, on the wall of each public school classroom in the State has no secular legislative purpose as required by Lemon; and, therefore, is unconstitutional as violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The Court stated:

- “The Commandments do not confine themselves to arguably secular matters, such as honoring one’s parents, killing or murder, adultery, stealing, false witness, and covetousness. See Exodus 20:12-17; Deuteronomy 5:16-21. Rather, the first part of the Commandments concerns the religious duties of believers: worshipping the Lord God alone, avoiding idolatry, not using the Lord’s name in vain, and observing the Sabbath Day. See Exodus 20:1-11; Deuteronomy 5:6-15….

- “Posting of religious texts on the wall serves no such educational function. If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. However desirable this might be as a matter of private devotion, it is not a permissible state objective under the Establishment Clause” (Ibid., p. 42).

The Courts opinion indicates that had the Kentucky statute left off the first four commandments (perhaps without the numbers so that no connection could be made to the commandments and God’s Word), those which deal with man’s relationship to God, the statute may have been constitutional. However, without all ten of the commandments being honored, without God being honored, students and other human beings are powerless to keep the last six commandments which deal with man’s relationship to man (prohibitions against murder, theft, adultery, dishonoring parents, lying, coveting). We see the results today in the zoos called public schools—murder, aggravated assault, lying, drug addiction, sexual sins of all kinds, prostitution, and all manner of evil. God told man the consequences of dishonoring the Sovereign of the universe. These undereducated judges had no idea about the consequences they were unleashing upon the American people.

In Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (1985), the Court held that, although a one-minute period of silence for meditation was constitutional, an Alabama law authorizing such a period is a law respecting the establishment of religion and thus violates the First Amendment. The Court used the Lemon test:

“Thus, in Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 612-613 (1971), we wrote:

‘Every analysis in this area must begin with consideration of the cumulative criteria developed by the Court over many years. Three such tests may be gleaned from our cases. First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion, Board of Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236, 243 (1968); finally, the statute must not foster `an excessive [472 U.S. 38, 56] government entanglement with religion.’ Walz [v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664, 674 (1970)]’” (Ibid., pp. 55-56).

Wallace stated that the Alabama law violated the first part of the Lemon test, noting that “[t]he sponsor of the bill that became [the law in issue] Senator Donald Holmes, inserted into the legislative record—apparently without dissent—a statement indicating that the legislation was an “effort to return voluntary prayer to the public schools” (Ibid., pp. 56-57).

In Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578, 107 S.Ct. 2673, 96 L. Ed. 2d 510 (1987) the Court held unconstitutional a Louisiana statute, the “Creationism Act,” which required the state’s public schools to give balanced treatment to creation science and evolution science. The statute did not require a school to teach either creation science or evolution science, but provided that if either one was taught, the other must also be taught. Edwards held that, although the Act’s stated purpose was to protect academic freedom, the actual purpose was to endorse religion, and therefore was in violation of Lemon’s first prong. The Court stated:

- “because the primary purpose of the Creationism Act is to endorse a particular religious doctrine, the Act furthers religion in violation of the Establishment Clause. The Act violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because it seeks to employ the symbolic and financial support of government to achieve a religious purpose” (Ibid., pp. 594, 597).

In reaching this conclusion, the majority opinion “reasoned:”

- “The preeminent purpose of the Louisiana Legislature was clearly to advance the religious viewpoint that a supernatural being created humankind. The term ‘creation science’ was defined as embracing this particular religious doctrine by those responsible for the passage of the Creationism Act. Senator Keith’s leading expert on creation science, Edward Boudreaux, testified at the legislative hearings that the theory of creation science included belief in the existence of a supernatural creator.… Senator Keith also cited testimony from other experts to support the creation-science view that ‘a creator [was] responsible for the universe and everything in it.’ … The legislative history therefore reveals that the term ‘creation science,’ as contemplated by the legislature that adopted this Act, embodies the religious belief that a supernatural creator was responsible for the creation of humankind.

- “Furthermore, it is not happenstance that the legislature required the teaching of a theory that coincided with this religious view. The legislative history documents that the Act’s primary purpose was to change the science curriculum of public schools in order to provide persuasive advantage to a particular religious doctrine that rejects the factual basis of evolution in its entirety. The sponsor of the Creationism Act, Senator Keith, explained during the legislative hearings that his disdain for the theory of evolution resulted from the support that evolution supplied to views contrary to his own religious beliefs. According to Senator Keith, the theory of evolution was consonant with the ‘cardinal principle[s] of religious humanism, secular humanism, theological liberalism, aestheticism [sic].’ … The state senator repeatedly stated that scientific evidence supporting his religious views should be included in the public school curriculum to redress the fact that the theory of evolution incidentally coincided with what he characterized as religious beliefs antithetical to his own. The legislation therefore sought to alter the science curriculum to reflect endorsement of a religious view that is antagonistic to the theory of evolution.

- “In this case, the purpose of the Creationism Act was to restructure the science curriculum to conform with a particular religious viewpoint. Out of many possible science subjects taught in the public schools, the legislature chose to affect the teaching of the one scientific theory that historically has been opposed by certain religious sects. As in Epperson, the legislature passed the Act to give preference to those religious groups which have as one of their tenets the creation of humankind by a divine creator” (Ibid., pp. 591-593). [Emphasis mine.]

In Edwards, the Court again substituted its religious preference for that of the majority of the people of a state. The preference of the Court was to remove the God of the universe, the Creator of all, from consideration in the public schools. The Court used its twisted interpretations of the First and Fourteenth Amendments to achieve its goal. The Court used its God-given free will to establish law that is already resulting in dire consequences and will ultimately lead to the total destruction of this nation. What better way for the god of this world to achieve his purposes than providing for the perversion of the minds of children who will one day be adults. There is nothing new under the sun.

The Court, in Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992), held that the long time tradition of inviting clergy to give invocations and benedictions at high school graduation ceremonies was coercive and therefore unconstitutional. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, wrote:

“[T]he school districts supervision and control of a high school graduation ceremony places public pressure, as well as peer pressure, on attending students to stand as a group or, at least, maintain respectful silence during the invocation and benediction. This pressure, though subtle and indirect, can be as real as any overt compulsion” (505 U.S. at 593).

- “So the nonexistent constitutional right not to feel uncomfortable trumped, in the Court’s logic, the First Amendment’s guarantee of the free exercise of religion, which Providence, Rhode Island, had exercised for a very long time” (Levin, p. 49).

The issue in Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow, 124 S. Ct. 2301 (2004) was whether the voluntary recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance, including the phrase “under God,” in a public school setting violates the establishment clause. The Justices were unanimous in ruling against Newdow, but the various opinions demonstrate the Court’s confusion. Justice Stevens ruled that Newdow had no standing, Justice O’Connor invented a new establishment clause test, Kennedy ruled against Newdow based upon lack of standing, and Thomas admitted that if the coercion test were honestly applied, the recitation would have to be struck down, arguing therefore that the establishment clause needed to be rethought by the Court. Rehnquist argued that the pledge was constitutional because “reciting the Pledge, or listening to others recite it, is a patriotic exercise, not a religious one; participants promise fidelity to our flag and our Nation, not to any particular God, faith or church” (124 S. Ct. at 2320).

Two 2005 cases which dealt with the issue of whether the Establishment Clause allows the display of a monument inscribed with the Ten Commandments on public property illustrate how far down the slippery slope to destruction this nation has fallen. In neither of those cases is there an establishment of religion. In each, there is an establishment of religion. As Douglas Laycock said, “With respect to new religious displays, the lesson to politicians is never to mention the religious reasons that are, in fact, the only source of pressure to create such displays; to talk blandly of the display’s alleged historical, cultural, or legal significance; to place some secular [or non-Christian religious] text or object nearby, whether or not it has any real relation to the religious display; and, whether plausible or not, to vigorously claim a predominantly secular purpose and effect” (Marty Lederman, “Doug Laycock on the Ten Commandments Cases,” July 5, 2005, on the web at http://www.scotusblog.com/movabletype/archives/2005/07/03-week/). A close examination of the cases reveals that Professor Laycock’s statement is totally accurate. Most, if not all but one, of the arguments for the commandments in the brief and amicus briefs for those in favor of the monuments emphasized that the monuments were not religious and had a secular purpose, while those against the commandments argued that the monuments were religious. Those for the displays made secular arguments, and those against the displays made religious arguments. God will not honor such insanity by “Christians.”

In Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005) a plurality of four conservatives, along with the liberal Justice Breyer, upheld the display. The plurality stated that the test laid down in Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971) was not useful in dealing with the sort of passive monument that Texas had erected on its capitol grounds. Instead, in holding that the Establishment Clause allowed the display, the analysis used by the Court looked to the monument’s nature and the nation’s history. In McCreary County, Kentucky, et al. v. American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky et al, 545 U.S. 844 (2005)McCreary, the Court, using the test laid down in Lemon, declared that since the County’s purpose for the display was religious, the display was forbidden by the Establishment Clause.

In Van Orden Chief Justice Rehnquist, a conservative, joined by Justices Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas noted that the Ten Commandments monolith challenged was one of “17 monuments and 21 historical markers commemorating the ‘people, ideals, and events that compose Texan identity located upon the 22 acres surrounding the Texas State Capitol’” (Van Orden, 545 U.S. at 681). The court stated that the attempt to reconcile the strong role played by religion and religious traditions throughout the nation’s history with the principle that governmental intervention in religious matters can itself endanger religious freedom, “requires that we neither abdicate our responsibility to maintain a division between church and state nor evince a hostility to religion by disabling the government from in some ways recognizing our religious heritage.” The church who is to be divided from the state in this case is not there. The Court effectively declared that God is severed from the state and that the display was a mere historical marker which they would allow in this limited factual situation.