A Publication of Churches Under Christ Ministry

- Click here to go to the written lessons.

- Click here to go to the 3 1/2 to 6 minute video lectures.

- For accompanying study from God Betrayed click here.

Previous Lesson: IV. The Story of the Pilgrims Who Arrived in America in 1620, the Mayflower Compact

Next Lesson: VI. The Theology and Goals of the Puritans in America

Click here for links to all lessons on The Pilgrims and Puritans in New England.

Jerald Finney

Copyright © February 24, 2018

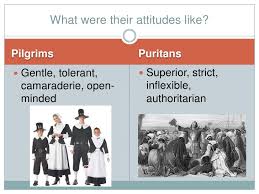

The Puritans, unlike the Pilgrims who wanted to separate from the Church of England, wanted to purify the Church from within. “The State, in their view, had the duty to maintain the true Church; but the State was in every way subordinate to the Church.”[1]

King James I was far more belligerently opposed to the Calvinistic church-state than even Queen Elizabeth had been, and his “determination toward the Puritans was to make them conform or to harry them out of the land.”[2] The Puritans who suffered under the combined pressure of accelerated persecution and the advanced moral decay in their society began to flee England for the new world.[3] “There was no ground at all left them to hope for any condescension or indulgence to their scruples, but uniformity was pressed with harder measures than ever.[4]”

Cheating, double-dealing, the betrayal of one’s word were all part of the game for London’s financial district. Mercantile power brokers loved, honored, and worshipped money, and accumulated as much of it as possible and as fast as possible. The ends justified the means. “London was an accurate spiritual barometer for the rest of the country, for England had become a nation without a soul.”[5] England was morally awful, and this came about under the auspices of a state-church practicing its theology.[6] 1628 marked the beginning of the Great Migration that lasted sixteen years in which twenty thousand Puritans embarked for New England and forty-five thousand other Englishmen headed for Virginia, the West Indies, and points south.[7]

A young Puritan minister named John Cotton preached a farewell sermon to the departing Puritans:

- “He preached on 2 Samuel 7.10 (KJV): ‘Moreover, I will appoint a place for my people Israel, and will plant them, that they may dwell in a place of their own and move no more; neither shall the children of wickedness afflict them any more, as beforetime.’

- “‘Go forth,’ Cotton exhorted, ‘… With a public spirit,’ with that ‘care of universal helpfulness…. Have a tender care … to your children, that they do not degenerate as the Israelites did….’

- “Samuel Eliot Morison put it thus: ‘Cotton’s sermon was of a nature to inspire these new children of Israel with the belief that they were the Lord’s chosen people; destined, if they kept the covenant with Him, to people and fructify this new Canaan in the western wilderness.’”[8]

The Puritans landed at Salem at the end of June, 1629. They were motivated by religious principles and purposes, seeking a home and a refuge from religious persecution.[9] Having suffered long for conscience sake, they came for religious freedom, for themselves only. “They believed [in] the doctrine of John Calvin, with some important modifications, in the church-state ruled on theocratic principles, and in full government regulation of economic life.”[10]

The Puritan churches “secretly call[ed] their mother a whore, not daring in America to join with their own mother’s children, though unexcommunicate: no, nor permit[ed] them to worship God after their consciences, and as their mother hath taught them this secretly and silently, they have a mind to do, which publicly they would seem to disclaim, and profess against.”[11] In 1630, 1500 more persons arrived, several new settlements were formed, and the seat of government was fixed at Boston. Thinking not of toleration of others,” they were prepared to practice over other consciences the like tyranny to that from which they had fled.”[12]

- Click here to go to the written lessons.

- Click here to go to the 3 1/2 to 6 minute video lectures.

- For accompanying study from God Betrayed click here.

- Click here for links to all lessons on The Pilgrims and Puritans in New England

Endnotes

[1] William H. Marnell, The First Amendment: Religious Freedom in America from Colonial Days to the School Prayer Controversy (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), p. 40.

[2] Ibid., p. 42.

[3] Peter Marshall and David Manuel, The Light and the Glory, (Old Tappan, New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1977), p. 146.

[4] John Callender, The Civil and Religious Affairs of the Colony of Rhode-Island (Providence: Knowles, Vose & Company, 1838), p. 66.

[5] Ibid., p. 148.

[6] Ibid., pp. 147-148.

[7] Ibid., p. 148

[8] Ibid., p. 157.

[9] Roger Williams and Edward Bean Underhill, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience Discussed and Mr. Cotton’s Letter Examined and Answered (London: Printed for the Society, by J. Haddon, Castle Street, Finsbury, 1848), p. v.

[10] Marnell, p. 48.

[11] Williams and Underhill, p. 244.

[12] Ibid., p. vii.