A Publication of Churches Under Christ Ministry

Jerald Finney

Copyright © February 23, 2018

Many forces came together to bring lignt and religious freedom to America. The Protestant Reformation was one step in that direction, even though the resulting Protestant denominations took from the Catholic church the idea of the church-state—the church controls the state. The colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire established a church-state. England established a state-church—the state controls the church—and several of the early colonies in the South established a state-church.

Many forces came together to bring lignt and religious freedom to America. The Protestant Reformation was one step in that direction, even though the resulting Protestant denominations took from the Catholic church the idea of the church-state—the church controls the state. The colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire established a church-state. England established a state-church—the state controls the church—and several of the early colonies in the South established a state-church.

With the Reformation, new light was beginning to shine over the English speaking world. The printing press made it possible to print and distribute the Bible in large quantities to the general public. The Bible became available in English and all could compare what they were told with the Word of God. Of course, this would result in some heresies, but no heresy could be more contrary to the Word of God and more destructive to eternal life, temporal human life, and the glory of God than the heresies of the Catholic church. Alongside new heresies would continue the light of truth—which had before been attacked mercilessly by the establishment which had attempted to brutally stamp out those who preached and practiced it—about matters such as salvation, baptism, and the relationship of church and state. In the colonies men were beginning to study the Bible and to debate issues. Those debates were published and disseminated and the light of truth further extended.[1]

While the debate was going on in the colonies, dissenters were persecuted. These persecutions gradually began to soften even members of the established churches, as people began to realize that persecution did not stand up to the test of Bible truth. The Baptists were by far the most active of all the colonial dissidents in their unceasing struggle for religious freedom and separation.

Unlike those areas of the New World settled by Catholics where only Catholics could immigrate and hold offices, and where the official religion was maintained by the government, “the English statesmen opened the gates of their American colonies to every kind of religious faith that could be found in Europe.” Additionally, unlike church-state relationships in Spain and France where no significant change occurred, England experienced changes of religion, which ranged from Catholicism (which was a minute minority) to Puritanism during the colonization of America. As a result, only in Catholic Mexico and Catholic Quebec was uniformity of religion achieved.[2]

“The individualism of the American colonist, which manifested itself in the great number of sects, also resulted in much unaffiliated religion. It is probably true that religion was widespread but was mostly a personal, noninstitutional matter.”[3] This contributed to the growing movement toward religious liberty since “[p]ersons not themselves connected with any church were not likely to persecute others for similar independence.”[4]

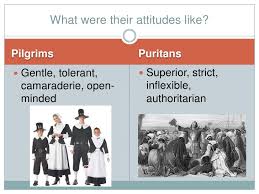

The tradition which the Puritans of England and later of New England inherited was that of Geneva, where the church absorbed the state and the church-state originated.[5] New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut had church-state establishments—the church used the state to enforce the Ten Commandments and dissenters were persecuted.

The Anglo-Catholicism of England[6] was later transferred to the southern colonies.[7] Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia had state-church establishments—the state was over the church.

“The Calvinists who governed New England and oppressed Anglicans were themselves persecuted in Virginia, and forced to pay taxes to support the hated Anglican establishment from which they fled.”[8] “[T]he Reformed Church was the state-church in New Amsterdam; the Quakers dominated Pennsylvania, … and, for a short time, the Catholics Maryland.”[9] In New England—Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Hampshire—Congregationalism was the established church. In Virginia and North and South Carolina, the Church of England was established. New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and Georgia experienced changes in church-state establishments. “In … Pennsylvania and Delaware, no single church ever attained the status of monopolistic establishment.”[10]

“From Maryland south to Georgia there were recurring periods of persecution and repression.”[11] In Maryland, the Calverts tolerated the Puritan settlers who later suppressed Catholicism. Anglicanism was established in 1689 after conflict in charters granted the second Lord Baltimore and William Penn.[12]

The Anglican Church was established in North and South Carolina much as in Virginia. However, dissenters were allowed to immigrate into those states due to the need for settlers. From 1700 on the major political conflict in South Carolina was shaped up around the conflict of the establishment and the dissenters, with the latter growing in the back country and a pronounced shift to Anglicanism on the coast. In 1704 a bill was jammed through to exclude all dissenters from the legislature. In 1706 the Church Act was passed, with dissenters excluded from voting; the land was divided into parishes…. Anglican clergy were frequently immoral and guilty of gross neglect of their people. In 1722 nearly one fourth of the taxes went to the established church. With independence in South Carolina came disestablishment.[13]

Emigrants from the persecuted Baptist church in Boston came to Charleston, South Carolina in 1683. The second Baptist church in South Carolina was Ashley River founded in 1736. By 1755, there were four Baptist churches in South Carolina and the second Baptist Association in America, the Charleston Association, was founded in 1751.[14] The General Baptists established several churches in North Carolina between 1727 and 1755. All but three of those churches converted to Particular Baptist churches in 1755 or 1756. By 1755, there were only twelve Baptist churches in North Carolina.[15] However, as will be seen, this was about to change with the arrival of some Baptists from Connecticut.

New York colonial history was unique in some ways. Until 1664, the Dutch reformed church was established and supported by the state. Imprisonment was required for those who failed to contribute to the support of the church minister. All children were required to be baptized by a Reformed minister in the Reformed Church. Only the Reformed, the English Presbyterians, and the Congregationalists could build church buildings. Lutherans were imprisoned for holding services and Baptists were subject to arrest, fine, whipping, and banishment for so doing.

In 1664, New Amsterdam surrendered to the English, and New York extended its jurisdiction over all sects. The Protestant religion, and not one church, was established as the state religion. The head of the state was head over every Protestant church. All Protestant churches were established. Only four counties conferred preferential status upon the Church of England after attempts to confer such status throughout the state were unsuccessful.[16]

“In New Jersey agitation by Episcopal clergy for the legal establishment of the Church of England failed to attain even the partial success achieved in New York.”[17]

“In Georgia, the original charter of 1732, which guaranteed liberty of conscience to all persons ‘except Papists,’ was voided in 1752, and the Church of England was formally established.”[18] Nonetheless, Georgia had a history of public hostility toward dissenters even before the church-state establishment. Jews and Moravians were persecuted to the extent that nearly all of these peoples fled that state in 1740 or retreated to their own enclaves. “In 1754, the colony reverted to the status of a royal province and several efforts were made to enforce the Anglican establishment.”[19] There were no Baptist churches in Georgia in 1755.[20] In 1758 the law of Anglican Establishment was passed. By 1786 there were not over five hundred active Christians in Georgia: “there were three Episcopal parishes without rectors and three Lutheran churches, three Presbyterian churches, three Baptist churches—all small and struggling.”[21] The Constitution of 1798 provided for complete religious freedom including Catholicism.

Maryland, established in 1631 and settled by both Catholics and Protestants, practiced a degree of toleration. Catholics attempted to procure the preferred position possessed in European countries with Catholic establishments, but they were unsuccessful since they were never in the majority. Although the Maryland Act of Toleration of 1649 has been lauded as “the first decree granting complete religious liberty to emanate from an assembly,” “even a superficial examination of the law shows quite clearly that it is far from a grant of ‘complete religious liberty.’” The first three of the four main provisions of the act “were denials rather than grants of religious liberty; only the last four dealt with toleration.” The first imposed death for infractions such as blasphemy, denying Jesus Christ to be the son of God, using or uttering any reproachful speeches, words or language concerning the Holy Trinity,” etc. The second imposed fines, whipping, and imprisonment on any who called another any one of certain names. The third imposed fines or imprisonment for profaning the Lord’s day. By 1688, the Anglicans had the upper hand and the Church of England was established in Maryland.[22]

Pennsylvania, like Maryland was colonized partly as business venture and partly as a “holy experiment.” The proprietor of the colony, William Penn, joined the Quakers while a student at Oxford. Penn opposed coercion in matters of conscience and provided for it in the fundamentals of the government of Pennsylvania. “Nevertheless, profanity was penalized, and Sunday observance for church, scripture reading, and rest was required. Political privileges were limited to Christians, and complete freedom of worship, at least at the beginning, was not allowed Catholics or Jews. As in Calvert’s Maryland, Penn’s motivation was at least partly his desire to reap substantial profits and this required attracting large numbers of settlers.[23]

King James made New Hampshire a royal colony in 1679. Liberty of conscience was allowed to all Protestants, but the Church of England was “particularly countenanced and encouraged.” Each town in New Hampshire determined the church to be supported with its tax revenues. Dissenters, with submission of a certificate proving regular attendance and financial support of a dissenting church, were exempted from the tax. However, the assembly was slow to accord financial recognition to dissenting sects.[24]

The stand of the dissenters, especially the Baptists, in the face of persecutions in the colonies gradually turned public opinion against persecution and toward religious freedom. Bible believing Baptists who stood in word and deed against colonial establishments eventually prevailed. Baptists proved to be loyal to the nation in the American Revolution was another factor which tipped the scale toward those freedoms protected by the First Amendment.

Endnotes

[1] God assures man, in His Word, that one can find truth. “Then said Jesus to those Jews which believed on him, If ye continue in my word, then are ye my disciples indeed; And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (Jn. 8.31-32). “Sanctify them through thy truth: thy word is truth.” Believers are told to “Study to shew thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth” (2 Ti. 2.15). Catholicism would have one believe that only the clergy has the God-given ability to understand Scripture—such a belief assures the power of the clergy, but the loss of God’s power. The Jews at Berea were commended for studying the Scriptures: “These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures daily, whether those things were so” (Ac. 17.11).

[2] Leo Pfeffer, Church, State, and Freedom (Boston: The Beacon Press, 1953), pp. 74, 83.

[3] Ibid., p. 85.

[4] Ibid.

[5] William H. Marnell, The First Amendment: Religious Freedom in America from Colonial Days to the School Prayer Controversy (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), p. 32, 33, 37. In the English colonies, unlike in Mexico and Quebec, no single faith dominated the others throughout the colonies and religious uniformity was very limited. On the European Continent, “the Reformation from the start was an effort to return the Church itself to the doctrines and practices of its apostolic days.” However, while discarding some of the heresies of the Catholic “church,” Protestantism, under pressure from civil governments, soon resumed the Catholic conceived theology which united church and state. The final, logical thought of the reformers was reached at Geneva, where the church absorbed the state and the church-state originated. The state became an aspect of the church.

[6] In England, the problem was to “wean the Church in England away from the Pope, but otherwise to leave it as little changed as possible.”[6] The monarch created the state-church and became the head of the church. The church became an aspect of the state. The king was the final authority on church doctrine and practice. “[T]he Church in England [became] the Church of England, [and] the Church [became] an aspect of the State.”[6] Under Queen Elizabeth, such Catholic doctrines as transubstantiation, the communion of saints, and purgatory were abandoned and the Mass was labeled a “blasphemous fable and dangerous deceit,” but ecclesiastical organization remained mainly unchanged, and episcopacy was its principle. Because she wanted a united state, Queen Elizabeth wanted a church where the Anglo-Catholics and the Anglo-Calvinists could worship together.

[7] Ibid., pp. 37-38.

[8] Pfeffer, p. 65.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Franklin Hamlin Littell, From State Church to Pluralism: A Protestant Interpretation of Religion in American History (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1962), p. 12.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 14.

[14] James R. Beller, America in Crimson Red: The Baptist History of America (Arnold, Missouri: Prairie Fire Press, 2004), pp. 139-140, 142.

[15] Ibid., pp. 141-142.

[16] Pfeffer, pp. 70-71.

[17] Ibid., p. 71.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Littell, p. 15.

[20] Beller, America in Crimson Red, p. 142.

[21] Littell, pp. 16-17.

[22] Pfeffer, pp. 71-75.

[23] Ibid., pp. 78-79.

[24] Mark Douglas McGarvie, One Nation Under Law: America’s Early National Struggles to Separate Church and State (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005), p. 153.